As Evidence Action, we implement rigorously evaluated development programs, such as the Deworm the World Initiative and Dispensers for Safe Water. Together, these programs serve over 200 million people this year.

Scale is all about execution. This means constantly evaluating and improving our programs. We collect data on our key performance indicators, in order to make data-driven and evidence-based decisions on what aspects of our work are going well and which we need to change.

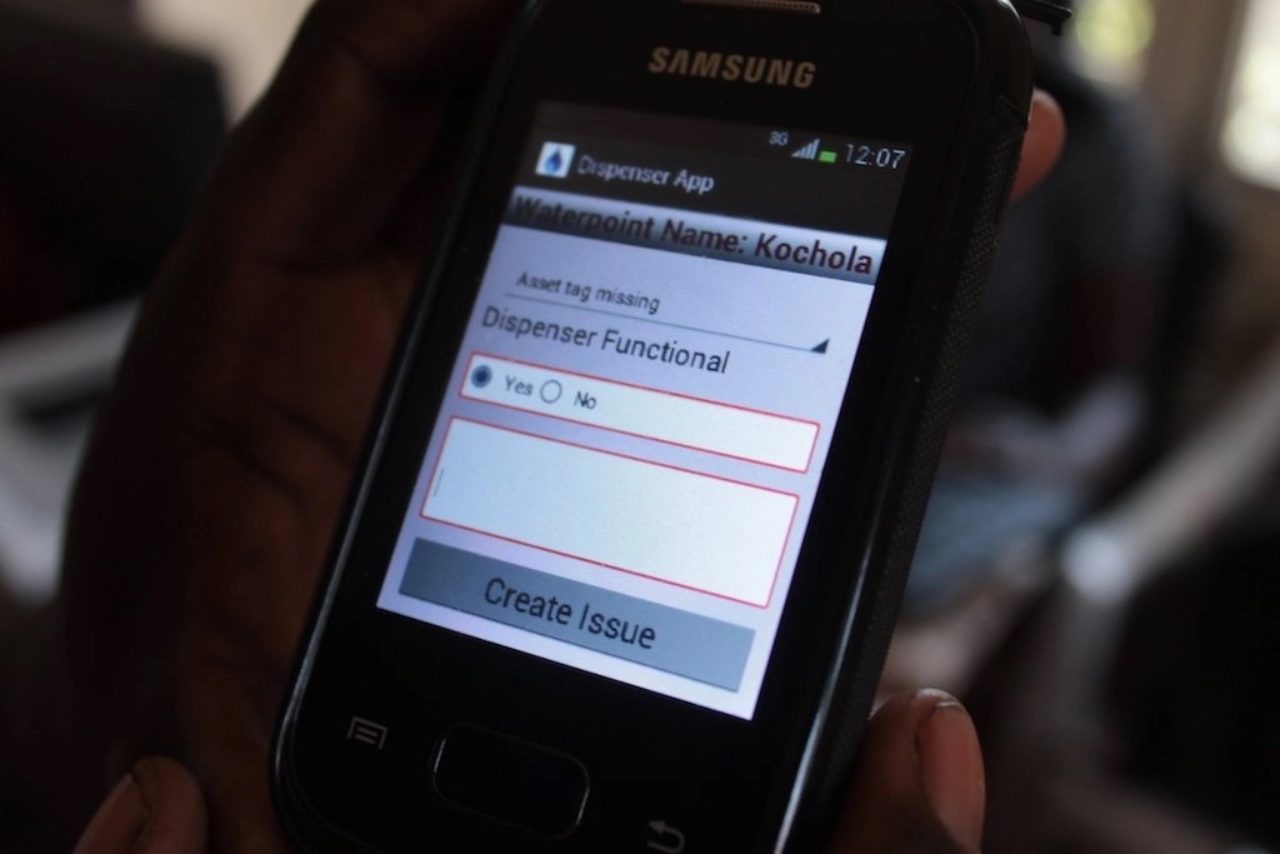

We collect data in a variety of ways but have been pushing hard to increase real-time, tech-enabled monitoring of our performance, and quick, streamlined, and action-oriented analysis.

We would love to collect all of our performance data electronically, but paper still prevails, and we are nowhere near 100% tech-enabled performance monitoring.

Here is what we are doing, with a frank assessment on how it’s going.

Paper versus Electronic Monitoring

Technology allows organizations like us to monitor our performance, make decisions about our programs, and report on our progress cheaper, faster, and better. The transparency and accountability that real-time monitoring and responsiveness enables is, in fact, a core value of Evidence Action. For instance, you can see how Dispensers for Safe Water is doing on this dashboard that draws data on key performance indicators that we are measuring for the program. This includes data points on how many people we are serving, the number of dispensers installed, and their uptime — all drawn directly from the MLIS database which, in turn, receives this data from mobile surveys in the field.

That said, we also work with very large institutions like ministries of health and education – government entities that work at much greater scale, have budget constraints and significant procurement restrictions, and are slower in their ability to change processes.

Imagine, for instance, trying to collect data electronically with millions of frontline teachers and preschool teachers – many of which may not have a phone or airtime readily available. This is precisely what we do in India – and paper, in these instances, just scales better right now

Open Data Kit

We use Open Data Kit (ODK) in East Africa and Malawi for our mobile surveys for both of our flagship programs there, the Deworm the World Initiative, and Dispensers for Safe Water.

ODK is a free and open-source set of tools which manage mobile data collection extremely well. We use ODK Build to convert paper questionnaires to e-forms and e-surveys. We then install ODK Collect on smartphones for our data collectors in the field. They use that to pull and push forms and surveys to and from a cloud data repository called ODK Aggregate that collates and stores forms in tables. Aggregate data tables can be downloaded in useful formats for deeper analysis, and other data processing.

ODK provides us with a data collection platform to effectively and efficiently monitor several key programs. It also improved the quality of our performance monitoring data. For instance, ODK ensures that all data collected and received is complete by prompting collectors to mark forms as finalized before they send them. If a form is not marked as finalized, then it cannot be sent to the repository. Additionally, structured surveys and logical and error checks reduce data errors that would be much more common in paper surveys.

For Dispenser for Safe Water, for example, we measure and record chlorine residual in the water of households that we visit. This gives us a clear indication of how many households in a community use their local Dispenser for Safe Water. Because we use ODK to record and transmit that data, we are able to get data on this key performance indicator in less than a day after our field workers have visited a household. If we find that chlorine use drops, we can immediately increase our outreach and engagement with that community.

Using ODK brings in such field data faster and with fewer errors, and gives the program leads a more timely assessment of how we are doing. As a result, we are able to make quicker decisions to adjust our programmatic responses.

We are also testing SurveyCTO, a mobile data collection platform that uses ODK, to complete a census and baseline survey for a deworming study in Western Kenya. According to our program lead, “It’s a fantastic platform, allows us to do everything we need, and has great support!”

Our Challenges

We would love to replace our paper surveys entirely with electronic field data but have run into some challenges. For instance, we work in some areas where there is poor connectivity and we have seen data get lost. Data collectors also have to have phones or tablets, and the power and airtime to run them. When we work with partners and at scale, this is not always possible.

For the Deworm the World Initiative in Kenya, teachers record the number of children treated with deworming drugs on paper forms in their classrooms. Not all teachers have mobile devices, computers, or internet to fill out these forms digitally so paper continues to be the most reliable way to get accurate deworming treatment numbers across the country even as the Kenyan government has made great strides to aggregate data in country-wide online health and education monitoring databases.

When we run very large surveys with very large sample sizes and many data collectors are fanned out across the country, we also use paper – simply because we do not have the capacity to provide our data collectors with a device. Data collectors also need to be trained on ODK and we need more qualified staff than we have to set up forms and run the software. Paper, in those cases, is the only feasible option.

Using SMS can avoid having to acquire smartphones, but SMS surveys are only suitable for smaller surveys. We are exploring this with state and the national government in India to gather rapid deworming coverage data from headmasters who send in a few key numbers (such as children dewormed per school, children absent, for instance) via SMS while more detailed data is recorded on paper by teachers in the classrooms and aggregated at the district and regional levels through an online database.

Our validation and independent monitoring surveys for deworming exercises, on the other hand, are complex and cover a lot of data points so an SMS survey is not suitable.

Lastly, paper can also be the best option when we are collecting data in sensitive areas, where using a phone can actually be counterproductive. In some areas where trust is low, for example, people are suspicious of data collectors taking photos , or are afraid that they might be unwantedly recorded. We opt for collecting data on paper in these contexts to ensure that people do not mistrust us and so that we get the relevant data we need.

What’s next?

As an evidence-based organization for which accurate and reliable data is critical, we continue to experiment with new ways to collect it. Whether it’s via SMS, USSD, IVR, mobile or tablet surveys, we are keen to continuously measure the key metrics that tell us how we are doing in our every-day work and whether we are having the impact we seek.

In the next few years, we will likely be streamlining some of our monitoring operations around the world as well as exploring new ways to make our key metrics openly available. We will also continue to explore with our government and NGO partners ways to collect data faster, cheaper, and better data – and explore new ways of using ‘big data’ to augment our own data collection. These are exciting times.

Editor’s Note: This blog post was written by Cherrelle Druppers, our Senior Associate for Data Innovation in our Monitoring and Information Systems Team in Nairobi.