If you woke up with a cold that would keep you home from work for three days, would you spend $18 on cold medicine to feel better by tomorrow? Most of us wouldn't think twice. That $18 just bought you back two healthy days – a simple trade we make without calculation.

But what if the stakes were higher? What if you could buy back not just days, but years of healthy life that people are losing right now to preventable disease?

For some, that question isn’t hypothetical.

Across the world, millions of people lose years of life to conditions we already know how to prevent or treat – often at an astonishingly low cost. Yet at the same time, an entire industry has emerged around extending life beyond what’s normal – searching for a few extra years when so many people still can’t live out the years they should. Tech entrepreneurs spend millions on longevity protocols. Investors pour billions into anti-aging startups and experimental treatments designed to stretch already-healthy lives a little longer.

This contrast raises an uncomfortable question: while the wealthy spend fortunes chasing extra years, how much would it cost to give back a healthy year to someone who’s losing one today?

At Evidence Action, we spend every day answering that question. We’ve vetted hundreds of potential interventions to find the most cost-effective ways to prevent years of life lost to disease. What we've found is startling: depending on the program and geography, it can cost less than $100 to restore a full year of healthy life.

In low and middle-income countries, millions of people lose years of healthy life to preventable diseases – conditions we know how to treat, at costs that seem almost absurd when placed beside longevity industry spending. A child dies from diarrhea caused by unsafe water. A newborn suffers lifelong complications from maternal syphilis that could have been detected and treated for less than $1. A pregnant woman develops severe anemia from easily preventable iron deficiency.

To measure and compare these health losses across different diseases and populations, the global health community developed a metric called disability-adjusted life years, or DALYs. It's the tool that allows us to answer precisely: What does it cost to give someone back a year of healthy life?

And the answer reveals one of the most dramatic inefficiencies in how we value health across the world.

What are DALYs?

Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) give us a way to measure the costs of both premature death and disability in a single metric.

The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study defines DALYs using “disability weights” – values derived from global surveys that capture how severely different conditions affect quality of life – where 0 equals perfect health, and 1 is equal to death.

Cost per DALY averted is a cost-effectiveness comparison tool, providing a lens for examining the cost to avert a year of death or disability. This is used as a fundamental metric in our Accelerator’s assessment process.

DALYs aren’t perfect. They don’t capture all dimensions of a given disease’s impact (e.g., economic costs; caregiver burden; or broader social impacts, such as how a depressed parent might affect their child’s life).

And disability weights are subjective. For example, when the methodology changed from expert panels to population surveys, major depressive disorder and blindness weights decreased, while chronic lower back pain and amputation increased. In addition, early versions of DALYs sometimes included age-weighting or discounting future years of life, sparking ethical debates. GiveWell’s 2008 blog series highlights additional dimensions of this discussion.

Despite its tradeoffs, the DALYs formula is still the best solution to act as a practical tool to quantify health, compare health interventions and inform resource allocation.

What DALYS Look Like at a Human Level

DALYs can sound abstract — a unit of measurement, a calculation. But behind every DALY averted is a child who stays healthy, a mother who brings her baby home, a life that unfolds as it should.

Ali's Story: Safe Water in Uganda

Ali is a one year old living in rural Uganda, where life expectancy is 70 years. For his family, the only water source is a borehole two miles from their house — water contaminated with E. coli that causes severe diarrhea.

Without access to safe water, Ali's childhood would follow a tragically common pattern: four separate bouts of diarrhea, each lasting several days, with his small body growing weaker each time. Before his fifth birthday, complications from his fourth episode would take his life. He would lose 65 years he should have lived.

With safe water from Evidence Action's in-line chlorination devices, Ali doesn't get sick. He grows up. Those 65 years aren't lost — they're lived.

But DALYs capture more than just mortality. They also measure the burden of illness itself — the days spent too weak to play, the meals he can't keep down, the developmental milestones delayed by repeated sickness.

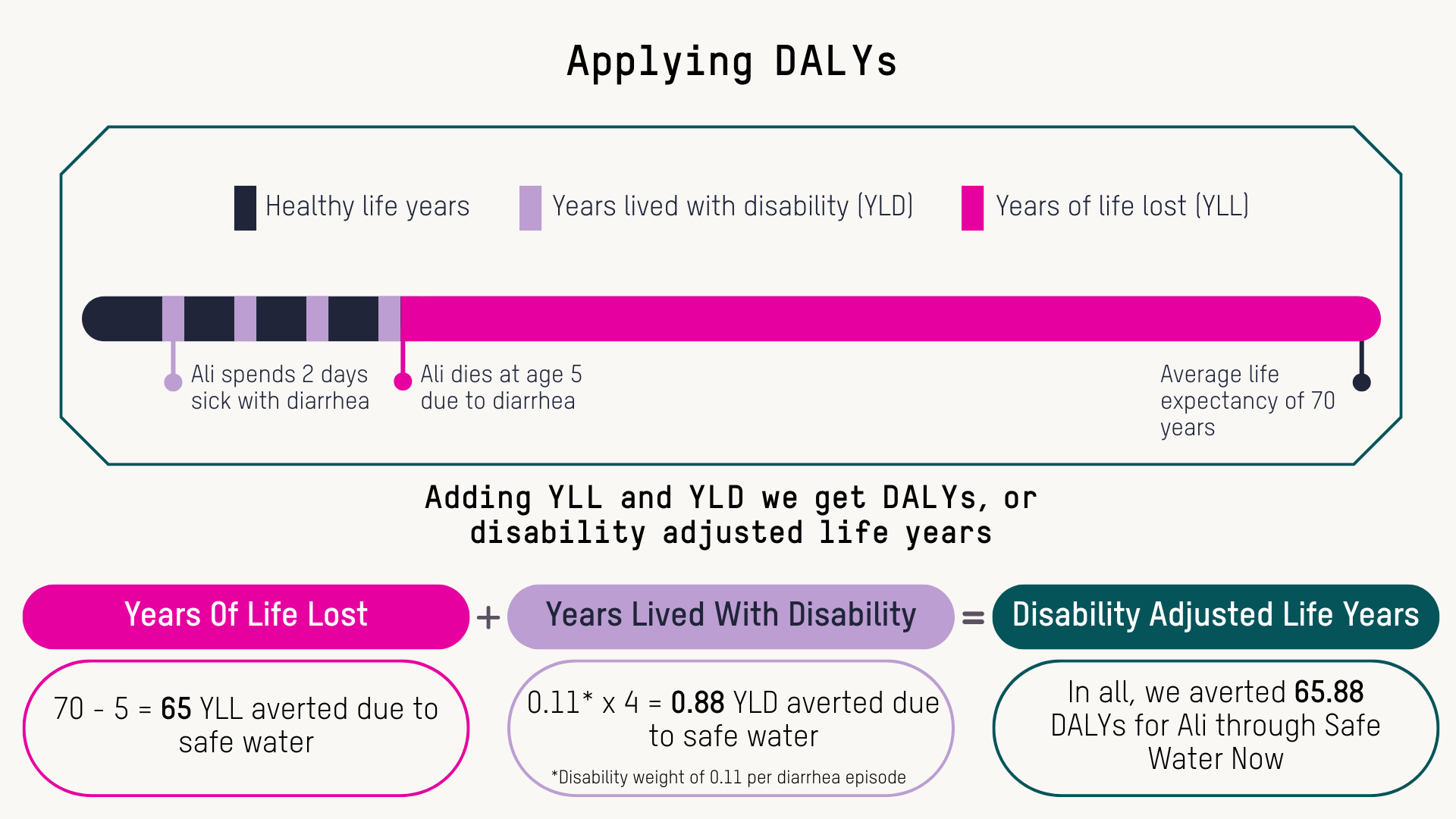

When we calculate Ali's DALYs averted, we account for both:

- Years of Life Lost (YLL): The 65 years between dying at age 5 versus living to 70

- Years Lived with Disability (YLD): The 0.88 years of healthy life lost to those four episodes of diarrhea (calculated using the disability weight for diarrhea severity and duration)

By providing safe water, we avert 65.88 DALYs for Ali. That single number represents a life saved and a childhood of unnecessary suffering prevented.

Preventing Congenital Syphilis in Liberia

DALYs work differently depending on the health challenge. Our Syphilis-Free Start program in Liberia – where syphilis affects about 3% of pregnant women – illustrates how the same framework applies to maternal and newborn health.

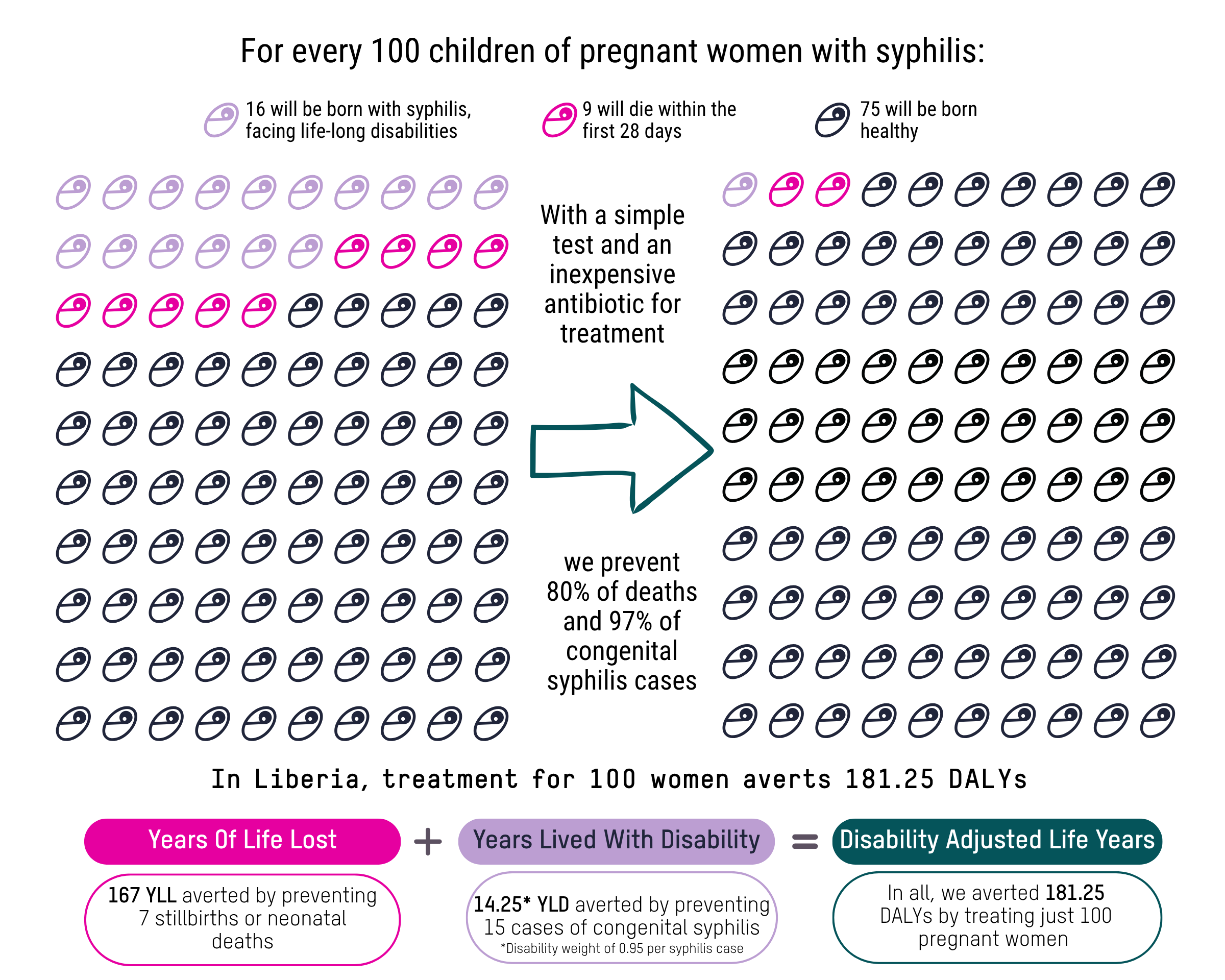

*This graphic is meant to help illustrate DALYs. This does not take into account other benefits of syphilis testing and treatment, which are included in our internal calculations to identify the cost-effectiveness of the program. If you are interested in a more detailed methodology, contact us at [email protected].

Without screening and treatment, the outcome follows a predictable pattern. Among 100 pregnant women with untreated maternal syphilis, 16 babies are born with congenital syphilis, suffering lifelong complications including developmental delays, bone deformities, and organ damage. Another 9 babies will die within the first 28 days of life.

With screening and treatment at Evidence Action-supported clinics, pregnant women receive a simple test and effective medication. The intervention is highly effective: it prevents 97% of congenital syphilis cases and 80% of stillbirths and neonatal deaths.

When we calculate DALYs averted, we account for both:

- Years of Life Lost (YLL): Each neonatal death prevented represents 23.89 years of life saved (based on life expectancy and standard discounting)

- Years Lived with Disability (YLD): Each case of congenital syphilis prevented averts approximately 0.95 years of disability, as the condition causes lifelong complications

For those 100 women receiving screening and treatment, we prevent:

- 9 stillbirths or neonatal deaths (saving 167 years of life)

- 15 cases of congenital syphilis (averting 14.25 years lived with disability)

The total impact: 181.25 DALYs averted – equivalent to giving back roughly 181 years of healthy life. Those 181 years across these families aren't lost — they're lived.

The Cost-Effectiveness Opportunity

That $18 you'd spend on cold medicine without thinking? In low and middle-income countries, it could restore weeks of healthy life. A $100 donation could restore more than an entire year in some countries.

At Evidence Action, we don’t pursue health interventions randomly. Through our Accelerator, we rigorously vet hundreds of potential programs, launching only those that meet our stringent cost-effectiveness standards. The result: A portfolio of interventions that represent some of the highest return health investments anywhere in the world.

How Do We Define "Cost-Effective"?

DALYs provide the measurement framework, but how do we determine which interventions are worth pursuing? The answer requires setting a threshold — a benchmark below which we consider a program cost-effective.

The World Health Organization recommends that interventions costing less than a country's GDP per capita are “highly cost-effective,” while those costing less than three times the GDP per capita are “cost-effective.” For the countries where Evidence Action operates, this translates to “highly cost-effective” WHO thresholds ranging from approximately $500 per DALY averted in Malawi to $2,700 in India (based on 2024 GDP per capita data).

At Evidence Action, we hold ourselves to a more stringent standard. Rather than evaluating programs country-by-country using WHO's approach, we first apply a country-agnostic threshold that is calculated as ½ of the average GDP per capita (or ¼ if looking at an even more conservative threshold) across countries where we work. This creates a more conservative baseline than WHO recommendations and ensures we're pursuing only the most cost-effective opportunities regardless of geography.

Why the stricter standard? Our goal is to save the most lives per dollar spent, agnostic of geography. A program that passes WHO thresholds in one country but not in another creates inconsistent standards. We use a set of conservative, geography-agnostic thresholds to determine what we believe to be a good use of Evidence Action resources, and to prioritize therein.

In addition to a program meeting our internal thresholds, we must also assess if this intervention is a good usage of resources in a particular country context. We work with country governments and partners to co-design and secure buy-in for programs, and to help understand our programming in the perspective of broader country priorities. We evaluate our cost-effectiveness analysis results for specific countries against a range of benchmark interventions and resources, including Disease Control Priorities 3, World Health Organization - Choosing Interventions that are Cost Effective (WHO-CHOICE), and unpublished league tables from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation on the cost-effectiveness of 132 interventions in 204 countries, in addition to GDP and opportunity-cost based thresholding. This dual approach ensures both global cost-effectiveness and local appropriateness.

Our Programs in Action

Each of these programs represents a different path to the same goal: restoring years of healthy life at costs that make every dollar count.

We’re fighting anemia before it starts.

Iron and folic acid deficiency affects millions of pregnant women and children, causing fatigue, developmental delays and complications during pregnancy. Through our Equal Vitamin Access program, we partner with governments to deliver supplements through schools and health facilities, reaching nearly 50 million children annually in India alone. For about $75 per DALY averted, this program averts 32,000 DALYs and saves 32 lives each year.

We’re preventing disabilities that begin before birth.

Maternal syphilis — detected and treated for less than $1 — can cause stillbirths, neonatal deaths, and lifelong complications for babies. Through our Syphilis-Free Start program in Liberia, integrating screening and treatment into routine antenatal care, we’ve averted more than 26,000 DALYs between 2020 and 2024. That’s 26,000 years of healthy life restored for mothers and newborns. At roughly $149 per DALY, this intervention remains one of the most cost-effective ways to prevent loss of life and lifelong disability in maternal and newborn health.We’re now identifying additional countries with high disease burden, strong antenatal care attendance, and low baseline screening rates — contexts where this intervention can be particularly cost-effective.

We’re expanding our approach to maternal nutrition.

Moving beyond iron and folic acid alone, multiple micronutrient supplementation addresses the complex nutritional needs of pregnancy — preventing low birth weight, premature births, and stillbirths. Our pilots show strong cost-effectiveness, with costs ranging from $75 to $243 per DALY averted depending on the country context.

We’re piloting programs that blend health and economic impact.

Our reading glasses pilot addresses presbyopia—age-related vision loss that affects people's ability to work and engage with daily life. Early modeling shows this costs around $197 per DALY averted while generating roughly $44 in additional earnings for every $1 spent, on average. A farmer who can see clearly works more productively. A teacher can continue in the classroom. These aren't just health gains — they're pathways out of poverty.

And then there’s Deworm the World, which takes a fundamentally different approach to measurement.

While deworming does improve health, the transformative impact is economic. Children who aren't sick from parasitic worms attend school more regularly, perform better academically, and earn significantly more as adults. Our modeling estimates that by 2042, the program's first decade will have generated over $23 billion in increased earnings for the 343 million children dewormed across our implementing countries. That's roughly $169 in lifetime earnings for every $1 spent on deworming.

Closing the Gap

Every year, billions are spent in pursuit of longer lives for the already-healthy, while proven solutions to prevent early death and disability remain underfunded. The world doesn’t need new frontiers in human longevity to add years of healthy life — it needs greater investment in what already works.

Through programs that deliver safe water, prevent maternal infections, and combat anemia and malnutrition, we’re restoring health where it’s been unfairly lost. These are not experimental ideas or future possibilities; they’re proven interventions reaching millions of people right now in the places that need them most.

The real measure of progress isn’t how far science can stretch the human lifespan, but how effectively we ensure every person has the chance to live out the one they already have — healthy, whole, and free from preventable disease.