Dispensers for Safe Water improves access to safe drinking water among rural communities in Sub-Saharan Africa by installing easy-to-use chlorine dispensers right next to communal water points, making it easy for community members to chlorinate their water. Water chlorination is a safe and effective way of improving water quality, killing pathogens that cause diseases like cholera and diarrhea. The program trains and deploys trusted community volunteers, known as “promoters”, to encourage community use of the dispensers and to ensure they are properly refilled and maintained. Since 2013, the program has grown significantly both in terms of user base and geographic coverage. We currently operate over 27,000 dispensers providing access to safe water for 4 million people in Kenya, Uganda, and Malawi at an annual cost of just $1.36 per person served. We’ve also prevented an estimated two million cases of diarrheal disease in children under the age of five to date, which is the second leading cause of death in under-five children globally.

In 2016, the Millennium Water Alliance (MWA) approached Evidence Action with an interest in piloting our safe water model in Ethiopia, where over 48 million people still lack access to safe water despite the monumental strides that have been made to tackle the issue there. MWA and their partners were interested in Dispensers for Safe Water as a high-impact, cost-effective, and scalable way of addressing acute diarrhea and communicable diseases like typhoid. One MWA program implementer, CARE International, had previously experimented with distributing powdered chlorine through government-employed health extension workers, but data from the initiative showed that this method of chlorine provision did not translate into increased chlorination rates among households, and contaminated water remained a problem. Dispensers for Safe Water’s approach seemed promising, eliminating the need for users to remember to regularly chlorinate their water at home as well as maintaining consistently high adoption rates. The conspicuous blue dispenser, located at the users’ regular water point, serves as an instant reminder, and the chlorination process is integrated into users’ routine water-fetching, simplifying the process of treating water.

For us, the partnership offered a chance to gauge whether another organization can implement the Dispensers for Safe Water model given our support in supplying the hardware, sharing implementation best practices, and supporting program monitoring. This differs from our typical model, where we undertake all aspects of implementation, monitoring, and follow-up in the communities we serve.

Evidence First

As a first step, we partnered with MWA, with CARE as MWA’s lead implementing partner, to conduct a preliminary feasibility study and small-scale pilot to better understand the context and assess the delivery model. Specifically, we wanted to know:

- What water treatment options are available in the target communities, whether they work, and if not, why not

- What opportunities there might be to partner extensively with the government to co-implement the program alongside MWA and its partners

- What are local demand and attitudes towards chlorine-based water treatment and consumption of chlorinated water (given the potential for aversion to the taste and odor of chlorine, for instance)

- What gaps exist in the local chlorine supply chain that might need to be bridged

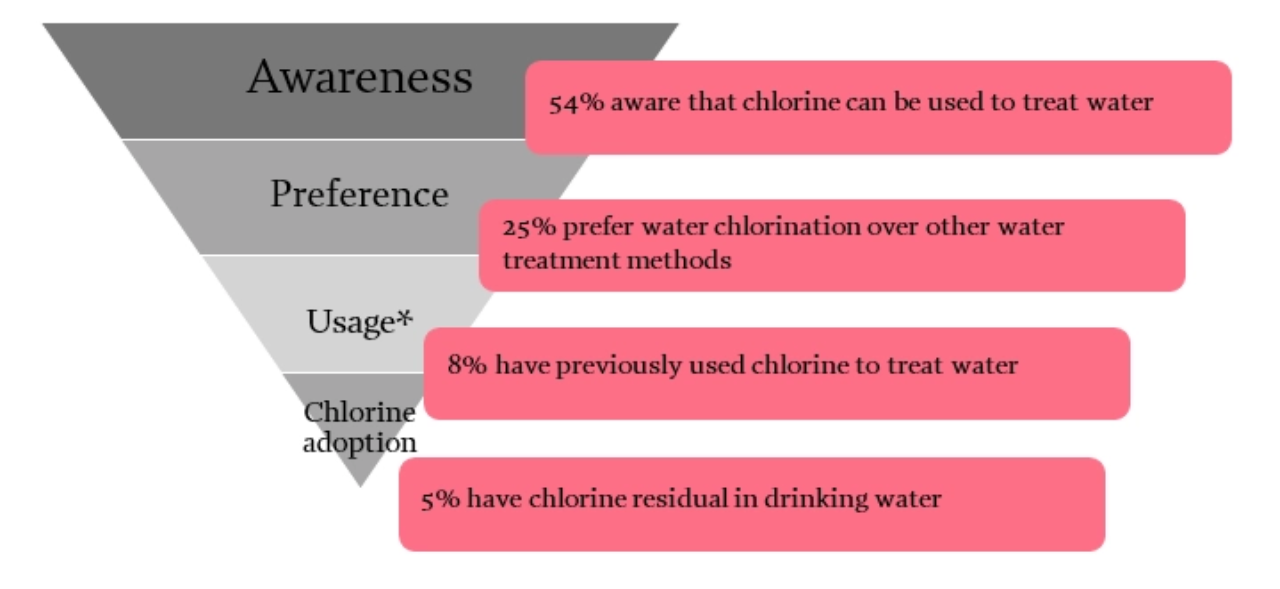

Our feasibility study, conducted in three kebeles (communities), found that only 22% of households took steps to make their water safe to drink. Of those, 81% boiled their water, which, while effective at killing pathogens, does not protect water from recontamination that can take place through poor water storage and retrieval practices. We also found that, although 54% of households were aware that chlorine could be used to treat water and 25% listed chlorine as their preferred water treatment method, 94% of households had never used chlorine to treat water. When asked why, nearly 90% of these households indicated that chlorine was not available to them.

To better understand what water treatment options were available in the market, we visited eight local retailers serving between 10 and 500 households and found that only one of them stocked water treatment products (WaterGuard and Aquatabs).

Recognizing a gap in available water treatment options that the Dispensers for Safe Water model could potentially fill, we initiated a small-scale pilot to learn more. Evidence Action supplied MWA with 49 dispensers for 3 districts (known as ‘woreda’) as part of MWA’s broader program to provide safe water or improved sanitation access to an additional 300,000 people in rural Ethiopia. We also trained government officials and implementing partner staff on how to install and maintain chlorine dispensers (including how to identify optimal sites for dispensers – locations where water sources serve a significant number of households and water is not too turbid to be treated by chlorine), how to educate the community about the new technology, and how to select and train volunteer community members to champion the use of the dispensers, keep them filled with chlorine, and report hardware issues.

Our support included designing the monitoring framework for the pilot and training CARE’s monitoring team on how to collect the applicable data. Meanwhile, chlorine was purchased locally, stored at government-run health centers, and regularly delivered to community-based volunteer promoters by government-employed health extension workers. The pilot ran from November 2016 to August 2017.

Promising Results

Before the pilot, baseline data showed that an average of 5% of households were using chlorine to treat their water. Data collected between April and July 2017, following the implementation of Dispensers for Safe Water, showed that, on average, 79% of households were using chlorine to treat their water. During the same period of time, the functionality rate of dispensers remained high, averaging 98% – which is critical since the regular use of dispensers often drops if hardware breaks or malfunctions and remains out-of-order for long periods of time. Based on our experiences in Kenya, Uganda, and Malawi, we also know that regular interaction between community promoters and the households they serve is associated with increased dispenser use. In the Ethiopia pilot, household survey results showed that “within the last 30 days”, 99% of households had seen their promoter and 98% of households had interacted with their promoter specifically about the dispensers. Additionally, households scored their promoters’ performance on average at 4.3 on a scale of 1-5 (with 5 being the highest score), with 96% of satisfied households attributing their satisfaction to the fact that “the promoter [taught them] how to use the dispenser.” Interestingly, word about the new chlorine dispensers spread beyond the communities in which the pilot was implemented, and we received anecdotal evidence of other communities asking local government officials to install dispensers in their areas too.

We will work with MWA to track these indicators over time. It is possible for initial community excitement at the introduction of a new technology to wane with familiarity. Similarly, promoters’ zeal to spread information, ensure dispensers are promptly refilled, and make certain that hardware issues are quickly identified and addressed, can fall too. Nonetheless, the early findings of the pilot remain encouraging. They suggest the potential for the Dispensers for Safe Water model to improve safe water access at larger scale in Ethiopia and that delivering the program through partners, with Evidence Action’s technical support, could prove useful for amplifying Dispensers for Safe Water’s impact.

Iterate, Again

Based on the promising results from the first phase of the trial, MWA has now kicked off phase two. The second phase involves installing 200 new dispensers and branching into new kebeles and woredas (districts), while following up with households from the first phase to track adoption rates (how many households continue to use the dispenser) and program quality (whether or not hardware has malfunctioned, whether chlorine is being promptly refilled when it runs low, etc.) over time. The second phase is slightly different from the first, as we iterate our way towards an effective delivery model at scale. One significant difference is that there are more MWA partners engaged in implementation, including Catholic Relief Services, Helvetas, and FH Ethiopia.

A second and more critical difference is that we are, for the first time, trialling a unique pay-for-chlorine system. Dispensers for Safe Water is typically a free service – a program design choice informed by extensive research showing the prohibitive effects of even small user charges for health products. However, our pilot partnership with MWA, with CARE serving as lead implementer, offers an opportunity to explore whether asking communities to pool together small amounts of money for the purchase of chlorine can work in a context where households are already paying a small amount to maintain their water sources and are asked to supplement this existing cost. In the current (second) phase of the trial, communities are beginning to contribute towards the purchase of chlorine, which is a promising start. However, we will monitor how this payment feature affects adoption rates over time and factor that data into our decision-making around whether to recommend its incorporation into the Ethiopia program, with a commitment to remaining evidence-based as we support MWA’s efforts to effectively address an urgent challenge facing millions of Ethiopians. As we continue to “test the waters” in Ethiopia, we will share updates on our progress and results.